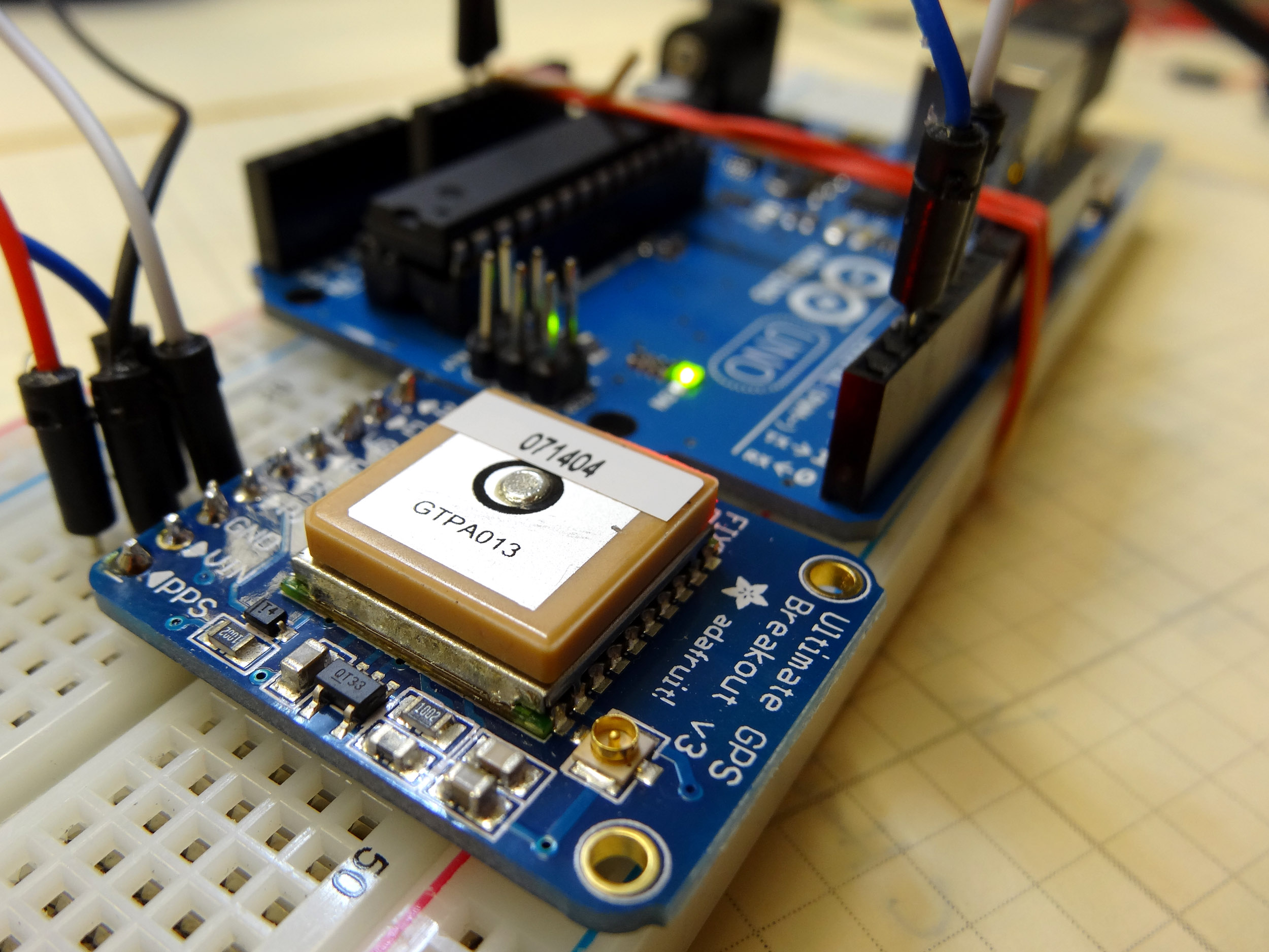

GPS units spit out data in a dizzying array of formats. It can become a challenge to take the output from a GPS unit, like the Adafruit Ultimate GPS breakout board, and get that data to play nicely with mapping programs like Google earth. It is as if no one is speaking the same language. In this lesson we will look at what the data coming off the GPS means, and how you can work with it, and get it to display properly in programs like Google Earth.

When you connect a GPS board up, and look at the data coming off of it, you are likely to see something like this:

$GPRMC,000009.800,V,,,,,0.00,0.00,060180,,,N*43

$GPVTG,0.00,T,,M,0.00,N,0.00,K,N*32

$GPGGA,000010.800,,,,,0,0,,,M,,M,,*41

$GPGSA,A,1,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,*1E

$GPRMC,000010.800,V,,,,,0.00,0.00,060180,,,N*4B

$GPVTG,0.00,T,,M,0.00,N,0.00,K,N*32

$GPGGA,000011.800,,,,,0,0,,,M,,M,,*40

$GPGSA,A,1,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,*1E

$GPRMC,000011.800,V,,,,,0.00,0.00,060180,,,N*4A

$GPVTG,0.00,T,,M,0.00,N,0.00,K,N*32

$GPGGA,000012.800,,,,,0,0,,,M,,M,,*43

$GPGSA,A,1,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,*1E

$GPGSV,1,1,00*79

This is what the data looks like when your GPS does not have a fix. When it does have a fix, there will be all types of numbers between the commas in the lines above. So, how do we make sense of all this? The first thing is to learn some of the lingo. Each line above is referred to as a NMEA sentence. There are different NMEA sentence type, and the type is indicated by the first characters before the comma. So, $GPGSA is a certain type of NMEA sentence, and $GPRMC is a different type of NMEA sentence. To make this whole thing a manageable problem, the first thing we must realize is that the data that we want will be in the $GPRMC sentence and the $GPGGA sentence. If your GPS unit has options to turn the other sentences off, then turn them off to simplify the data getting thrown at you. If you can not turn the other sentences off, then just ignore them, and focus on the two you care about, $GPRMC, $GPGGA.

If your GPS has a fix, then your GPS sentences should look something like this:

1 2 3 | $GPGGA,194530.000,3051.8007,N,10035.9989,W,1,4,2.18,746.4,M,-22.2,M,,*6B $GPRMC,194530.000,A,3051.8007,N,10035.9989,W,1.49,111.67,310714,,,A*74 |

Lets start by breaking down the $GPRMC sentence.

1 | $GPRMC,194530.000,A,3051.8007,N,10035.9989,W,1.49,111.67,310714,,,A*74 |

The $GPRMC is simply telling what sentence type is on the line. The next number, represents the Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). It works like this, 194530.000 would be 19:45 and 30.0 seconds in UTC. Since converting from UTC to your local time is simply a matter of knowing what time zone you are in, you can see that one thing you get from a GPS is a very accurate clock. The next letter just lets you know if your signal is Active (A) or Void (V). An ‘A’ indicates you are getting a signal and things are working properly. A ‘V’ means you do not have a signal.

Now, for the good stuff, the next number and following letter gives you your lattitude. 3051.8007,N should be interpreted as follows:

Your Latitude is: 30 degrees, 51.007 minutes, in the Northern Hemisphere.

Similarly, the next number, 10035.9989,W, is Longitude. This is interpretted as:

Your Longitude is: 100 degrees 35.9989 minutes, in the Western Hemisphere.

Degrees could be a one, two or three digit number. Hence you have to be careful parsing this data. What is always the case is that the first two numerals to the left of the decimal place, and the numbers to the right of the decimal represent the minutes. So, always take the number starting two to the left of the decimal, and those following all the way to the comma, and that is your minutes. Unfortunately, if you simply try to put 3051.8007,N,10035.9989,W, into Google Earth, it will not recognize it. The simplest thing you can do to get Google Earth to recognize and properly display the coordinate would be to enter the following:

30 51.8007N, 100 35.9989W

Notice the space inserted between degrees and minutes, and no comma before hemisphere designation. This would properly display that single point via the Google Earth search bar. The challenge however is that if you want to log data from your GPS and then show a track of where you have been, you will have to create a KML or KMZ file. These files are even more particular about the format of the coordinate data. These files want both latitude and longitude as decimal numbers, so we must convert degrees, minutes to decimal degrees. You can do this simply by realizing that there are sixty minutes in a degree. So, for the case above, 51.8007 Minutes = 51.8007/60 degrees = .86335 degrees. So, to make a KML file that Google Earth will like, 30 51.8007N should be converted to 30.86335. We still have to deal with the N and W. KML files do not know what to do with the N, S, E, W. So, you must do the conversion. On Latitude, if you have a N, leave Latitude positive, if you have a S make your Latitude negative. On Longitude, if you have an E leave your number positive. If you have a W make your Longitude negative. Following these rules:

1 | 3051.8007,N,10035.9989,W |

Should become:

30.8633, -100.5999

Those numbers will not only display properly in a KML file, they will also work if directly typed into the search bar on Google Earth.

We will talk more about KML files in the next lesson, but we will state here that in the KML file, you should put Longitude first, followed by Latitude. Opposite of how you put the numbers in Google earth, which wants latitude followed by longitude.

OK, that is the hard part, now for the rest of the characters in the sentence. The next number, 1.49 in the example above is the speed in knots. I was walking, so you can see this is a small number in the above example. The next number represents track angle, not something I find useful or use. Then after that, you see the number 310714. This is the date, which would be DD/MM/YY so this date is July 31, 2014. You can see on my NMEA sentence, I just get commas after that. Some units report magnetic variation here, but mine doesn’t. Then finally, the final characters represent a checksum, something we do not need to worry with.

So there, our first NMEA sentence parsed. You can see that you get just about everything you need in this one sentence.

So why do we need the $GPGGA sentence you ask. Well, it has a couple of nuggets of info we need, particularly if we are doing High Altitude Ballooning/Edge of Space work. Lets look at the $GPGGA sentence:

1 | $GPGGA,194530.000,3051.8007,N,10035.9989,W,1,4,2.18,746.4,M,-22.2,M,,*6B |

Again, the first number represents the time.

194530.000 would be 19:45 and 30.000 seconds, UTC

The next numbers represent Latitude and Longitude, just as in the $GPRMC sentence above, so I will not go through that again.

Now the next number, 1 above, is the fix quality. a 1 means you have a fix and a 0 means you do not have a fix. If there is a different number it is more details on the type of fix you have. Next number is how many satellites you are tracking. For us, 4. The larger number here the better. Next up, 2.18 is the horizontal dilution of position. Something I don’t worry with. Next one is an important one . . . 746.4 is my altitude in meters above mean seal level. This is hugely important for projects like high altitude ballooning. It is a direct indication of your altitude. Next number is the altitude of mean sea level where you are. This is something you do not need to worry about in most applications but is related to a geometric approximation of the earth as an ellipsoid. Look up WGS84 Ellipsoid if you really want to understand this number.

OK, lets bring this all home now. Using the $GPRMC and $GPGGA NMEA sentences, we can get our latitude and longitude coordinates, and convert them to numbers that can be recognized by Google Earth, or put into a KML file. We also have our speed in knots, and our altitude. These are all the things we would want for projects like unmanned aerial drones, or high altitude balloons.